March 2019 will be a month remembered for an unseasonably cold start, followed by an active and wet weather pattern which resulted in a continuation of excess soil moisture, and major flooding events on many local streams and rivers.

Statewide, March ended colder and substantially wetter than the long term average. The preliminary average statewide March temperature was 36.6°F, which is 4.7°F below the long term average. The preliminary average statewide precipitation was 4.16 inches, which is 1.20 inches above the long term average.

Data are provisional and may change slightly over time.

Temperature

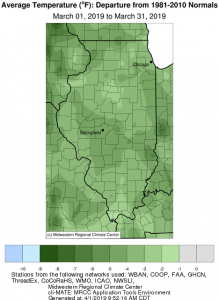

Preliminary results show that March 2019 finished with a statewide average temperature of 36.6°F which is 4.7°F below the long term average.

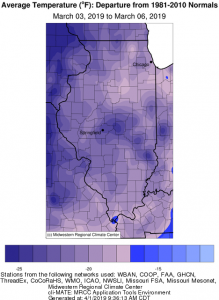

The first full week or March begun with a brutal Arctic outbreak in which temperature departures of 15° to 25° below normal were common across Illinois (see map below).

During this time three stations recorded minimum temperatures of -10° or colder. The lowest reading in the state, -12°F, occurred at the Little Red School House station (Cook County) on March 5th.

In contrast, the warmest reading in the state was 76°F, reported at a station near Dixon Spring (Pope County) on March 13th.

The map below depicts average monthly statewide temperature departures for Illinois. March temperature departures finished below average statewide, with the coldest departures occurring across large areas of central Illinois, and in the northwest corner of the state.

Precipitation

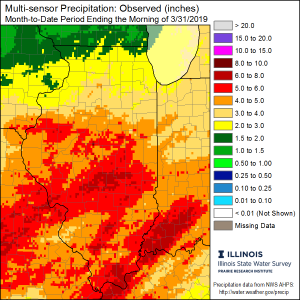

Preliminary statewide average precipitation for March was 4.16 inches, which is 1.20 inches above the long term average.

A persistent active weather pattern along with above average precipitation were the biggest weather stories in March. Major and historic flooding on the lower Ohio River Basin in Southern Illinois continued into the first week of March, resulting from substantial February rain events. By the middle of the month, a strong and historic low pressure system brought heavy rain, storms, and strong wind to Illinois and the rest of the Midwest. The heavy rains and combined regional snow melt resulted in additional widespread flooding concerns across the region. This included a major flooding event for northern and northwest Illinois, with the Rock, Fox, and Mississippi Rivers experiencing significant crests.

The heaviest March precipitation fell across central and southern portions of the state where 4 to 6 inches were common. Five stations in these regions reported over 6 inches of precipitation for the month. Totals were lower in Northern Illinois with generally 1.5 to 3 inches. The lowest totals for the month occurred along the Illinois/Wisconsin border.

The highest March precipitation total of 6.41 inches was reported at a station near Jerseyville (Jersey County).

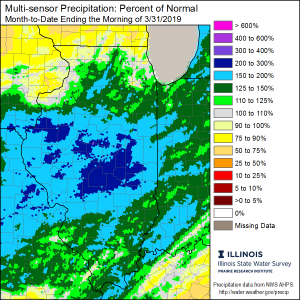

Above average March wetness led to precipitation anomalies over 100% of average for the southern two-thirds of the state, with the most impressive anomalies of 200-300% percent of average in a large area of central Illinois (see map below).

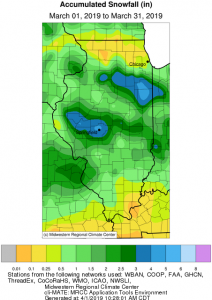

Snowfall in March did occur statewide, although it was rarely long lasting. Storm tracks are apparent on the accumulated snowfall map, with two distinct snow maximums. One in the vicinity of the corridor from Rushville to Springfield, and a second centered near Kankakee. In both cases 3 to 5 inches of accumulation were measured.

Spring Outlook

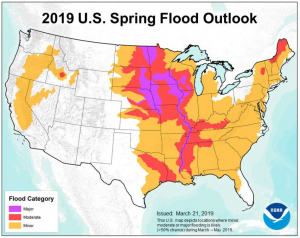

Soil moisture profiles across Illinois remain in the 90th percentile or higher as we head into April. This leaves soil conditions favorable for spring runoff, and is an ever-growing concern for the agricultural community.

The National Weather Service (NWS) spring flood outlook places the entire state in its flood risk zone. Eastern and central Illinois are subject to a minor flood risk, while western, extreme northern and southern portions of the state are in a moderate flood risk zone. Locations immediately along the banks of the Mississippi river are in a major flood risk zone.

April 2019

Looking ahead at the rest of April 2019, the Climate Prediction Center (CPC) is favoring probabilities of above average temperatures statewide. This is a welcome change compared to April 2018, which ranked as the second coldest April in state history. An active weather pattern looks to persist, as the April outlook favors slight probabilities of above average precipitation for the western half of the state.