The preliminary statewide average July temperature was 75.3 degrees, 0.1 degrees below the 1991–2020 average and tied for 64th warmest on record going back to 1895. The preliminary statewide total July precipitation was 5.08 inches, 1.02 inches above the 1991–2020 average and the 22nd wettest on record.

Data are provisional and may change slightly over time.

Mostly Mild July Capped by Big Heat

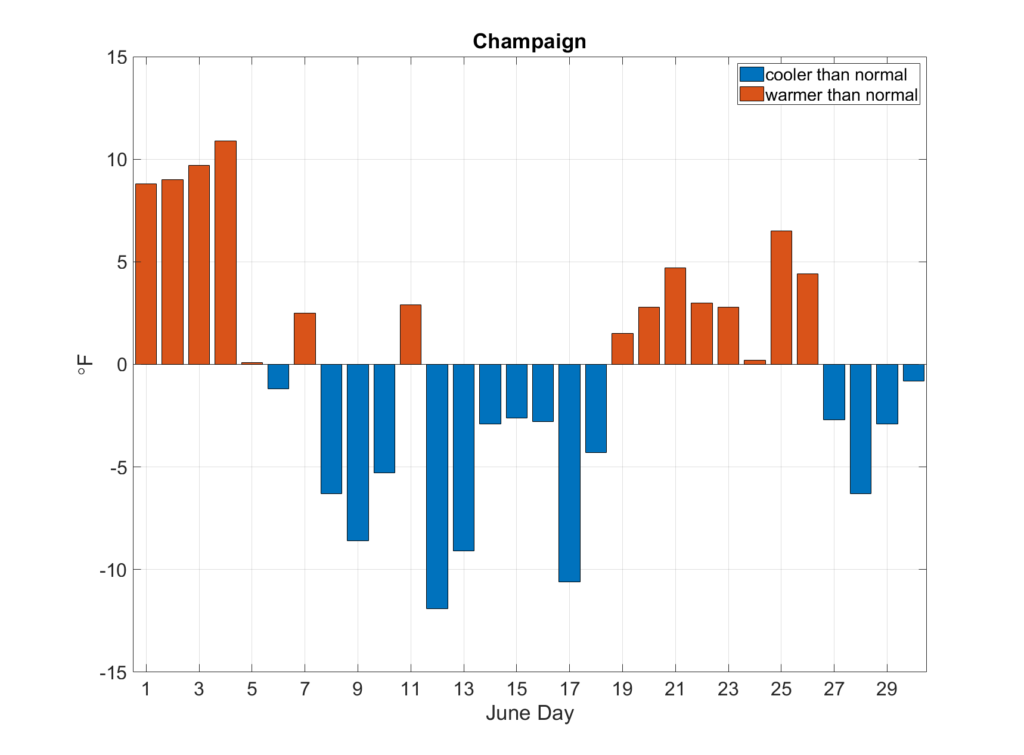

July began with a mix of slightly warmer conditions followed by a prolonged period of near to below normal temperatures. Temperature departures from Dixon showed a nearly three-week period where all but one day was cooler than normal in the middle of July (Figure 1). A large ridge over the southwest U.S. that kept a pleasant, northwest flow of cooler air into the Midwest for most of the month opened in the last week of July, building intense heat across the region between July 26 and 29. More details on the late July heatwave follow.

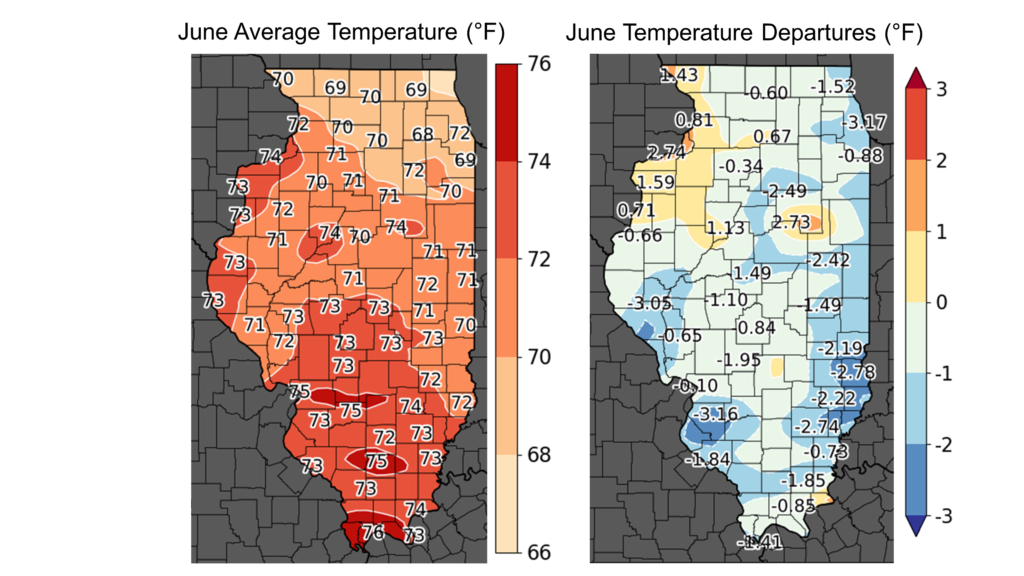

July average temperatures ranged from the low 70s in northern Illinois to the high 70s in southern Illinois, within 1 degree of normal virtually everywhere (Figure 2). The welcomed lack of humidity in the first two-thirds of the month allowed nighttime low temperatures to regularly dip into the low 60s and even 50s in some parts of the state. July nighttime lows included 51 degrees in Aurora, 53 in Chenoa, and 54 in Ottawa. Daily high temperatures were closer to normal, but rarely exceeded 90 degrees in the northern two-thirds of the state through most of July. The coolest place in the state last month was Stockton in Jo Daviess County with an average temperature of 70.5 degrees, and the warmest place in the state in July was Cahokia with an average temperature of 79.8 degrees.

Overall, the preliminary statewide average July temperature was 75.3 degrees, 0.1 degrees below the 1991–2020 average and tied for 64th warmest on record going back to 1895.

Extreme Heat in Late July

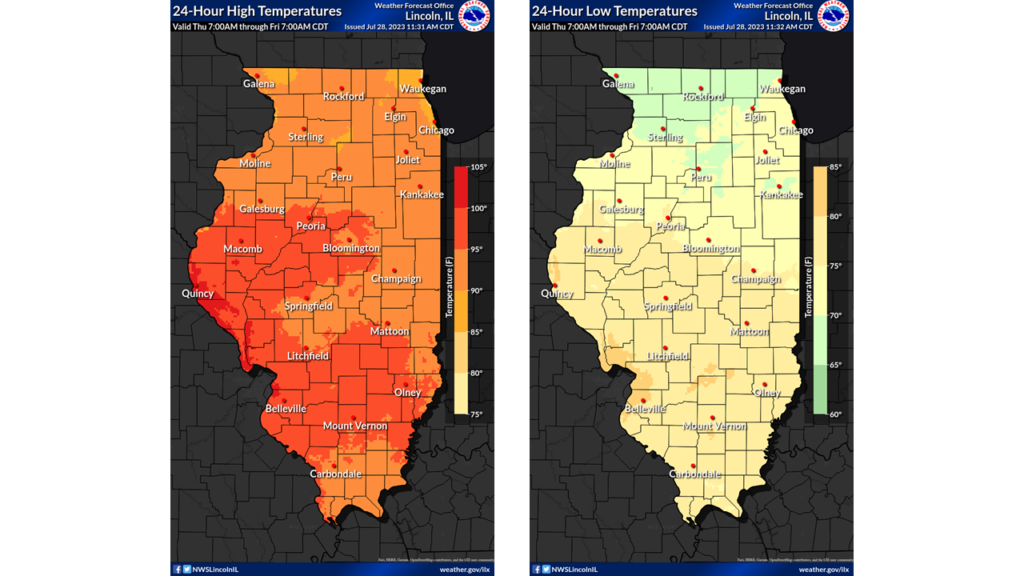

July is the climatologically warmest month of the year in Illinois and typically has the highest frequency of extremely warm weather. The heat in Illinois in the last few days of July, though, was unusual, even for our hottest month. Daily high temperatures on July 27 and 28 exceeded 90 degrees across the state and topped 100 degrees in parts of western Illinois (Figure 3). Combined with extremely high humidity, heat index values pushed well over 100 degrees and even exceeded 110 to 115 degrees in some parts of central Illinois. Champaign reached a heat index of 115 degrees and Decatur had an incredibly dangerous 120-degree heat index on the afternoon of July 27. The latter number is only the third day on record with a 120+ degree heat index in Decatur and the first day since 1999.

The maps in Figure 3 show that low temperatures overnight on July 27–28 only dipped into the mid-70s across much of the state, and a few places had nighttime lows at or above 80 degrees. The combination of very high temperatures–day and night–and relentless humidity presented extremely dangerous weather for humans and animals. Heat remains the deadliest weather hazard in the United States, but still doesn’t get as much attention as more visibly noteworthy hazards such as tornadoes and winter storms. Imagine if there were a community of “heat-chasers” who were equally passionate about documenting and warning of the impact of heat as storm chasers are for their hazards. Outside of health impacts, the heat buckled roads in central Illinois, forced the cancellation of many outdoor events and practices, and even forced a famed root beer stand in Peoria–one frequented by a certain State Climatologist–to temporarily shut down to protect workers. The heat also came at a busy time for farm workers, who remain one of the most vulnerable groups to heat-related health impacts in Illinois.

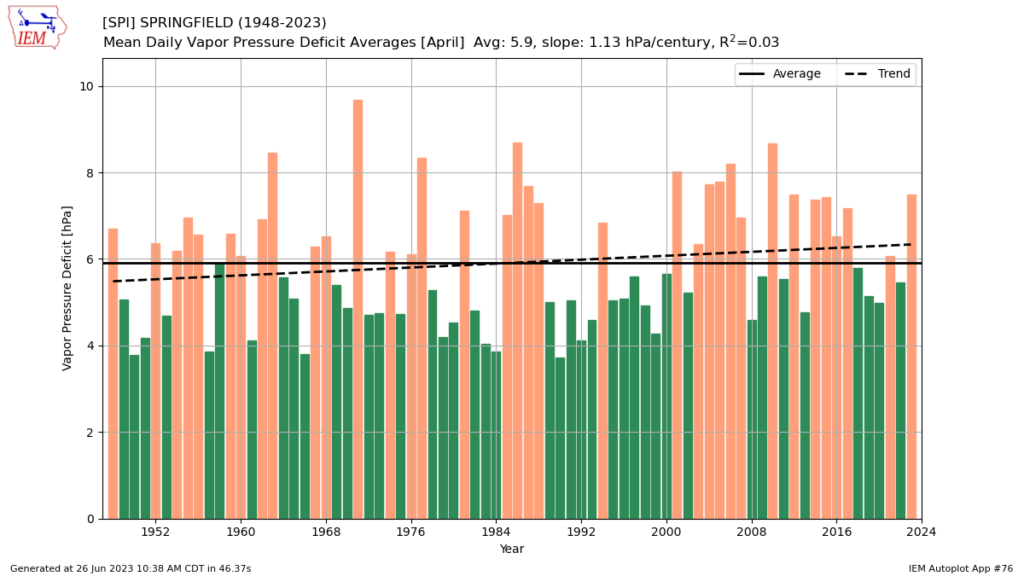

Climate change has increased the frequency and intensity of hazardous heat conditions in Illinois, as in much of the United States. Figure 4 shows summer average maximum and minimum temperatures in Cook County between 1895 and 2022, with black lines showing 30-year trends over the long-term record. The plots show nighttime minimum temperatures have been consistently warming over the 125+-year record in Cook County, and daytime maximum temperatures have been increasing consistently since the early 1950s. Both daytime and nighttime temperatures are important for human and environmental health impacts from heat. Recent increases and projected continued increases in both summer maximum and minimum temperatures increase exposure risk to extreme heat across Illinois.

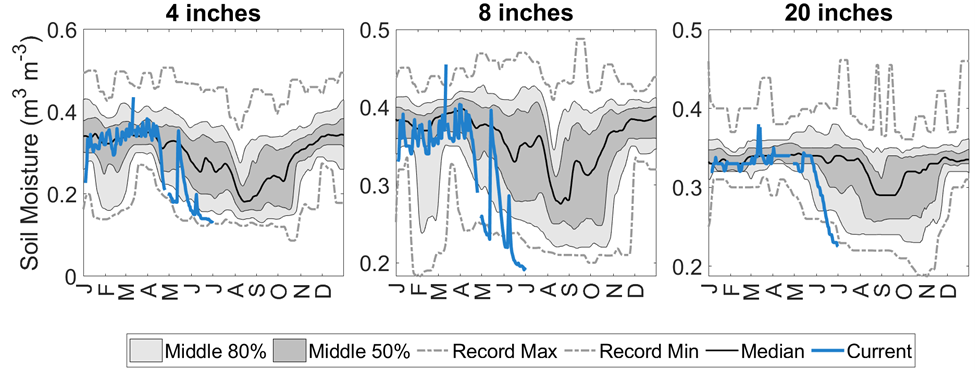

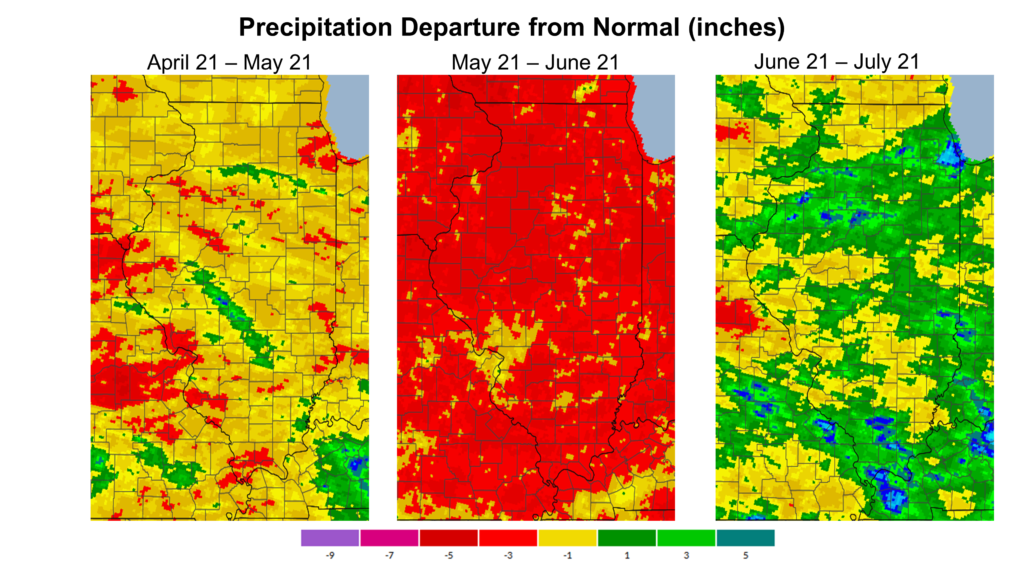

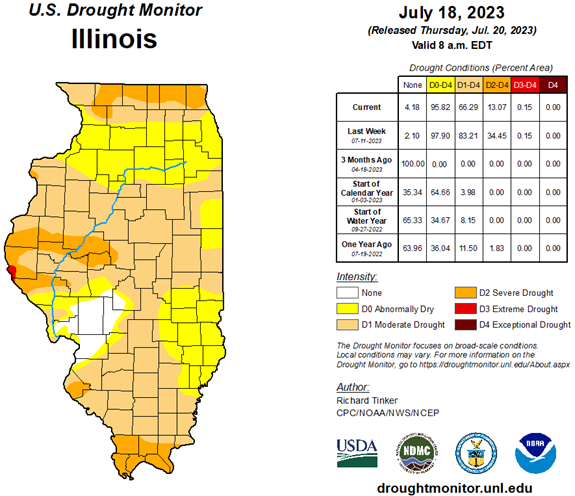

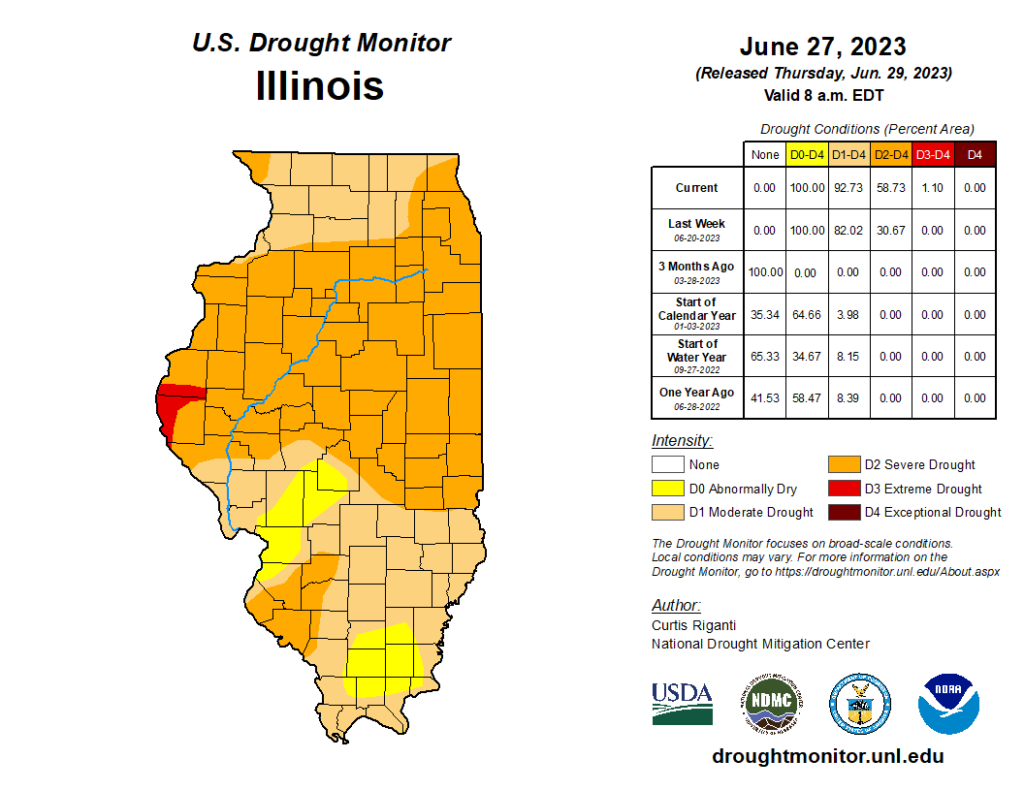

Some Drought Improvement with July Rainfall

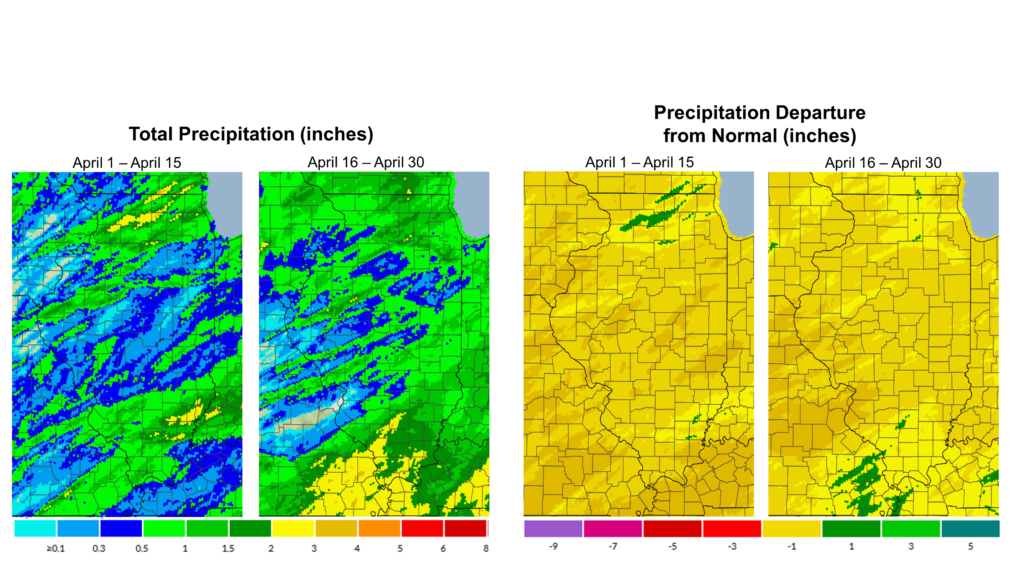

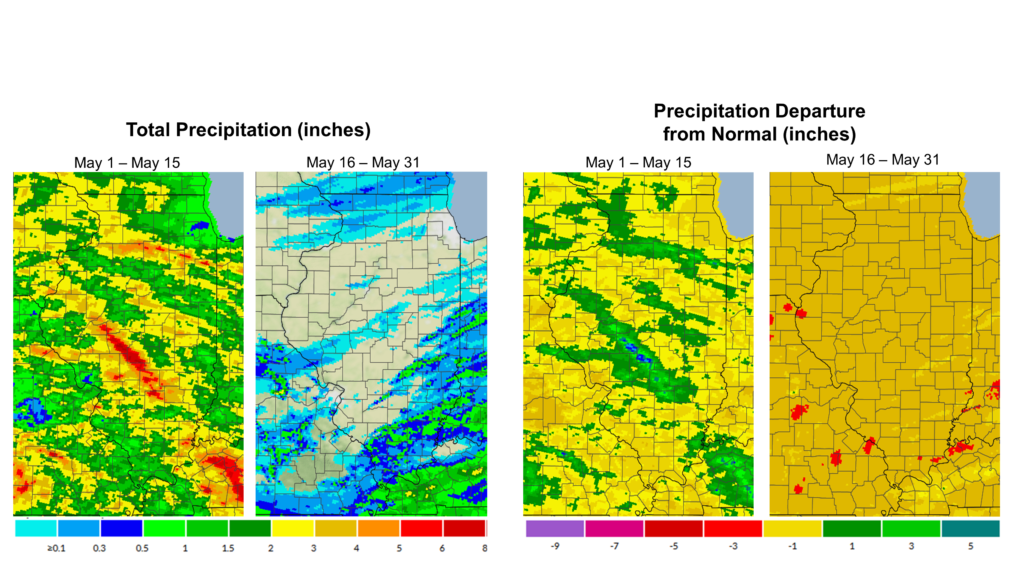

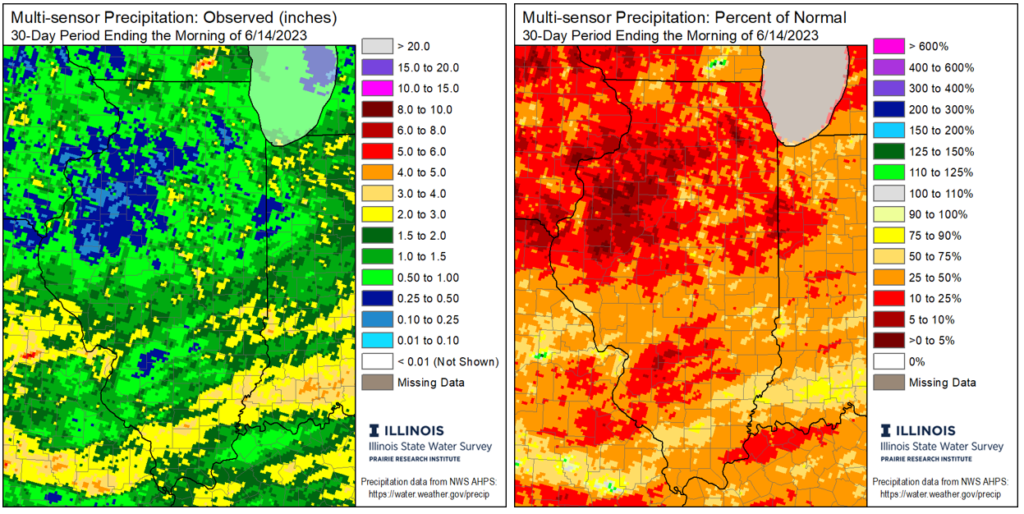

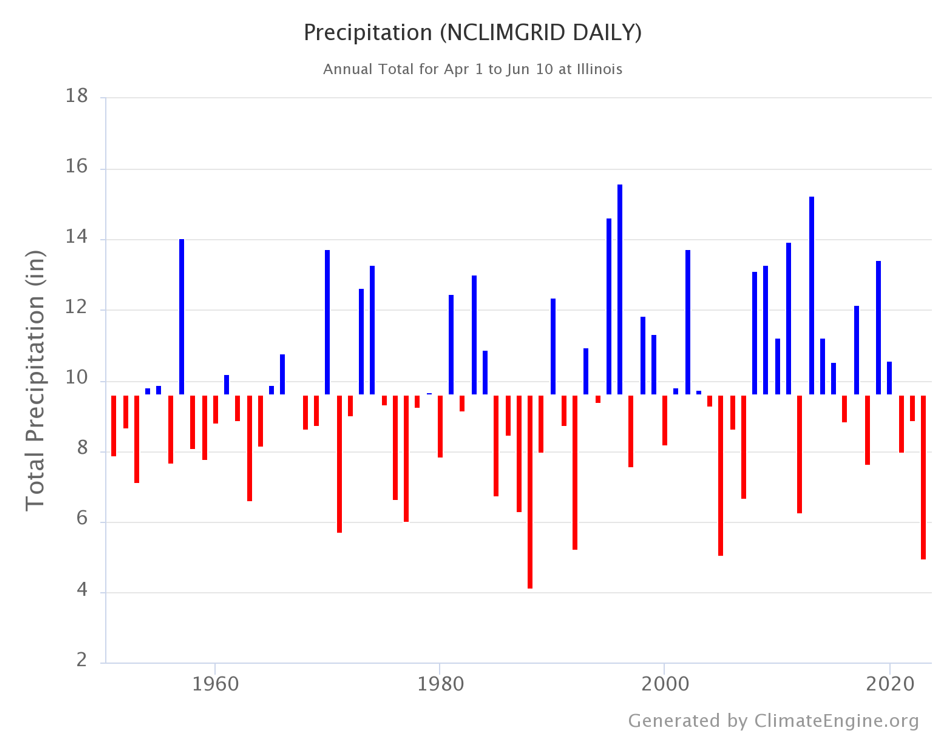

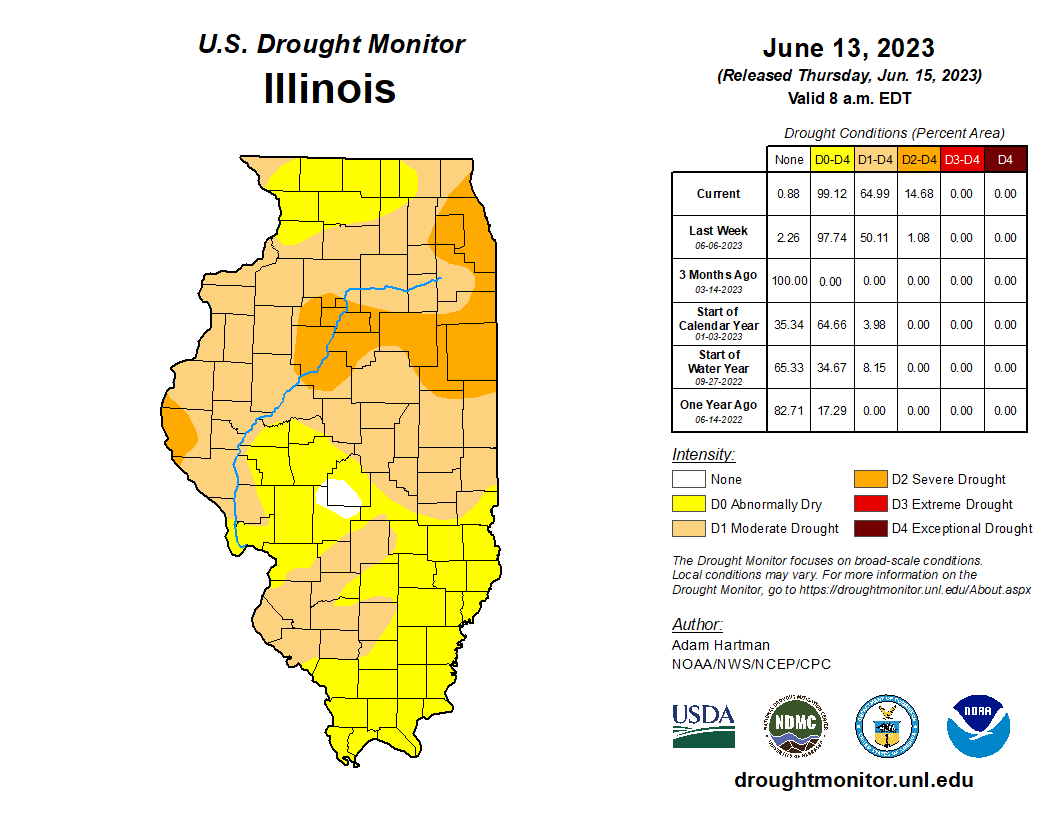

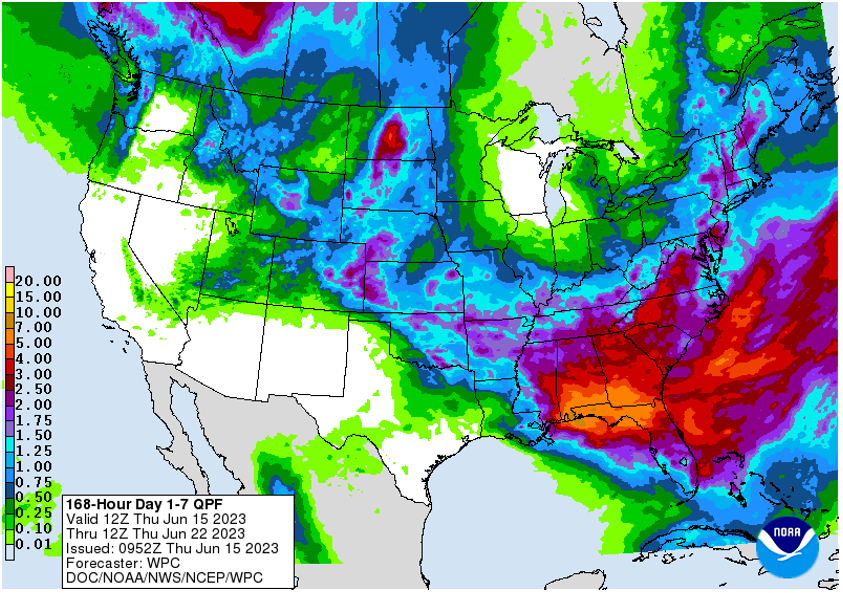

The period from April to June this year was the sixth driest on record statewide, and a top five driest on record in a handful of counties in Illinois. Moderate to extreme drought covered most of the state coming into July, and there were serious concerns of agricultural and hydrology impacts from the drought. July weather was somewhat to much wetter than the previous three months because of an active storm track coming over the ever-persistent ridge in the southwest U.S.

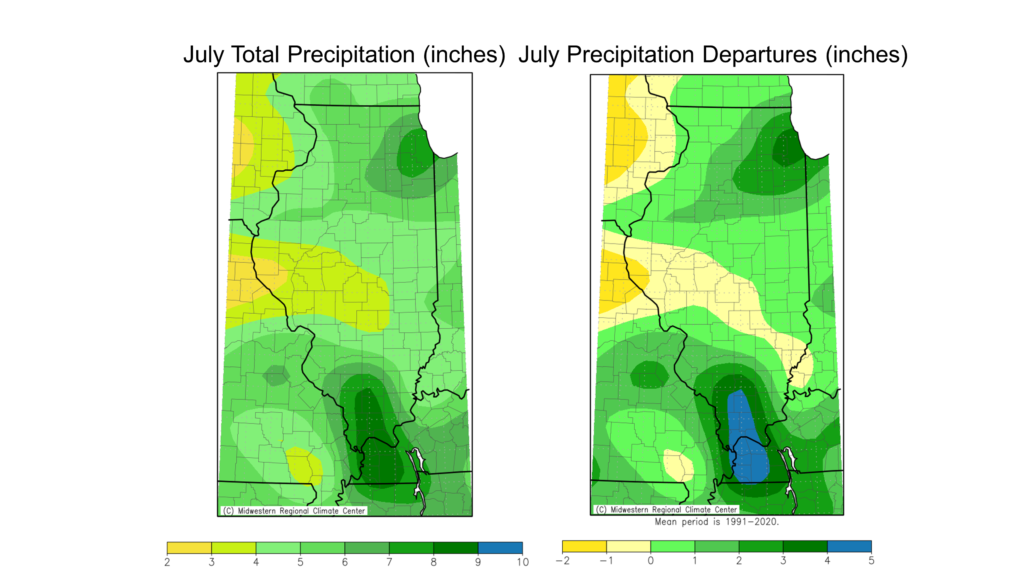

July precipitation ranged from around 2 inches in western Illinois to over 10 inches in parts of southern Illinois. The southern and northeastern parts of the state were 2 to 6 inches wetter than normal last month because of very heavy precipitation events that are detailed below. Meanwhile, much of central Illinois was within 1 inch of normal and western Illinois was somewhat drier than normal (Figure 5). Last month was the wettest July on record at Chicago’s Midway airport, following what was the fourth driest April to June on record there.

The preliminary statewide total July precipitation 5.08 inches, 1.02 inches above the 1991–2020 average and the 22nd wettest on record.

Heavy Rain in Chicagoland & Southern Illinois

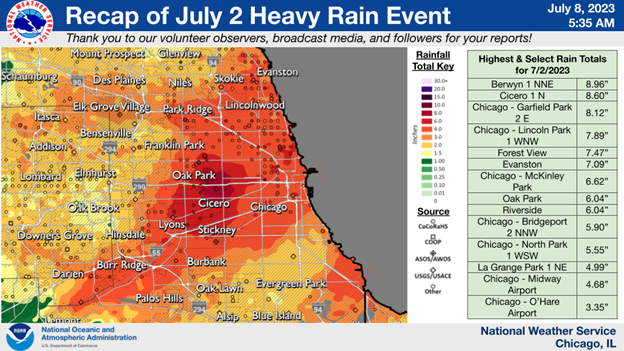

Meteorologists often quip that drought rarely breaks easily, referring to the alleged tendency for a drought to precede very heavy rainfall. The prolonged dryness in May and June in the Chicagoland area was indeed broken by a very intense rainfall event from a series of thunderstorms on July 1 and 2 (Figure 6). Among the highest 24-hour rainfall totals included 8.12 inches in Garfield Park, 8.6 inches in Cicero, and 8.96 inches in Berwyn. Based on the State Water Survey’s Bulletin 75 estimates, the event exceeded the estimated 1% annual exceedance probability storm (i.e., the 100-year storm*) in a few places. The heavy rain inundated stormwater systems and caused widespread flooding across the city, with thousands reporting flooded basements in Chicago alone.

*Two important caveats: 1) the “100-year storm” has a 1% chance of happening any given year, not once every 100 years, and 2) research has shown storm totals are increasing across Illinois, with a significant contribution from climate change.

Never to be outdone, southern Illinois decided to get in on the heavy rain action and experienced an incredibly intense series of training storms on July 18 and 19. Parts of Williamson, Johnson, Pope, Alexander, and Pulaski counties picked up over 8 inches of rain in less than 24 hours, with rainfall rates exceeding 3 inches per hour. Flash flooding occurred across the region, including at the Massac County Youth Fair (Figure 7). The event brought even more rain to western Kentucky and may have broken the Kentucky state record 24-hour rainfall total, with a preliminary 12.76 inches measured in Graves County. The measurement will need to be validated by a records committee before becoming official.

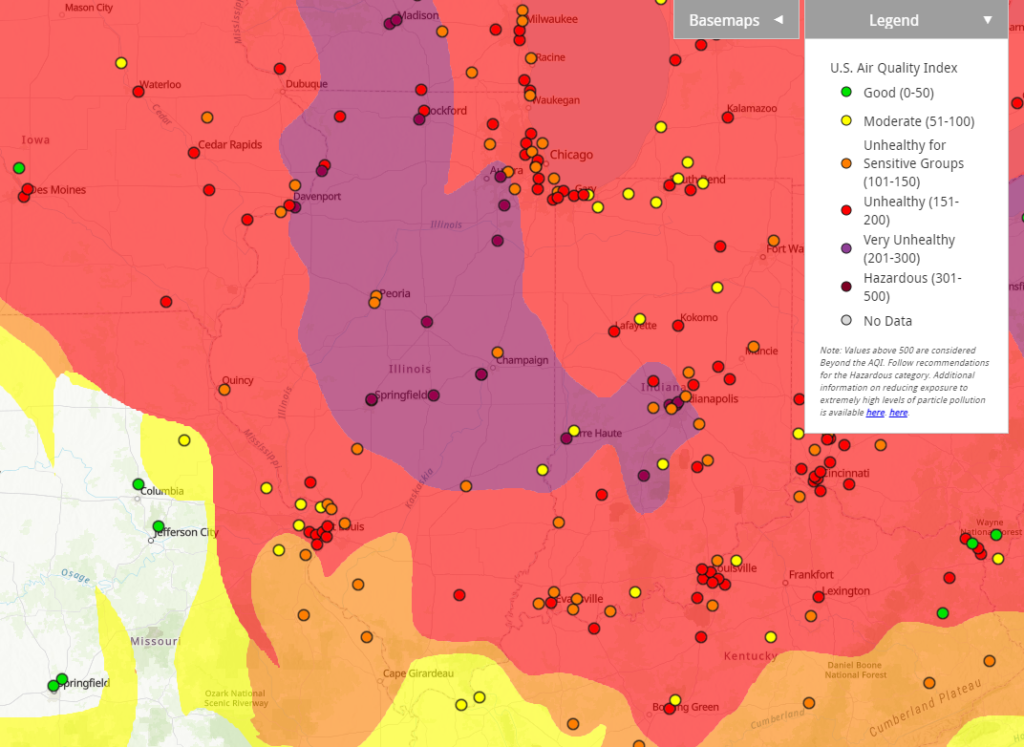

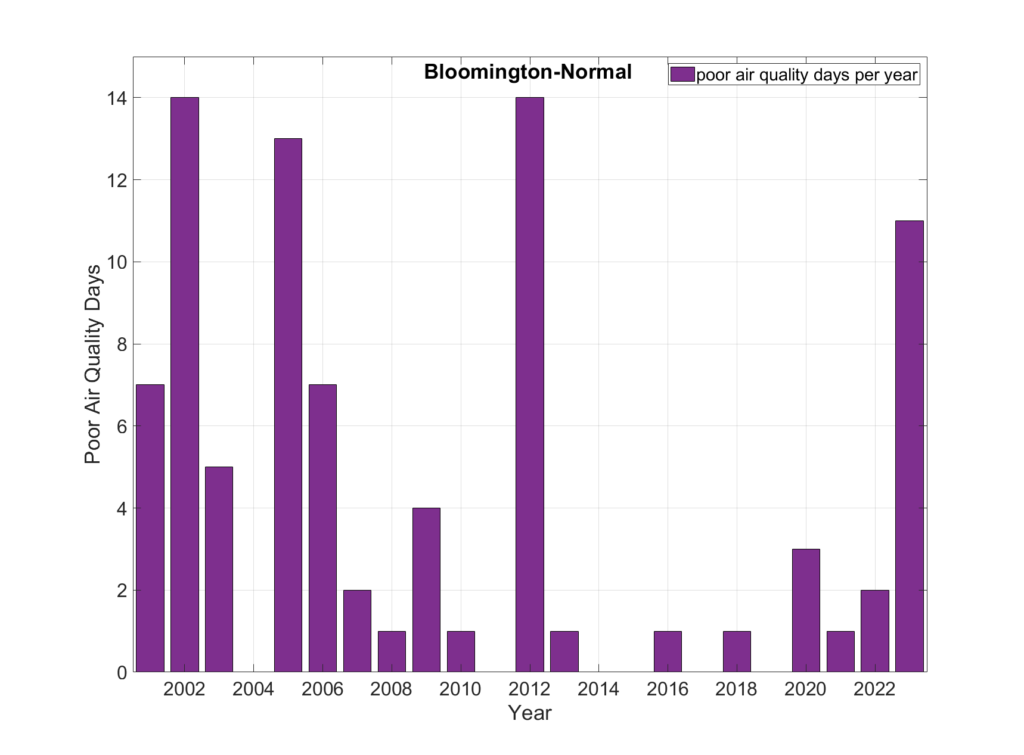

July Gave Out Free Smoke

As wildfires continued to burn across Canada in July, the Midwest ephemerally suffered from poor air quality as a result. While not quite as intense as in late June, much of northern and central Illinois experienced multiple days of unhealthy air quality last month. Figure 8 shows the number of poor air quality days (EPA Air Quality Index > 100) in Bloomington-Normal each year through July 31. Past drought years like 2012 and 2005 stick out with relatively frequent poor air quality days. However, the primary pollutant in these years was surface ozone, which is created effectively at very high temperatures that often correspond with drought. This year our high surface ozone levels have been augmented by high particulate matter from Canadian wildfire smoke.

As with extreme heat, health impacts from poor air quality are felt largely by folks most vulnerable to environmental hazards, including those experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity, those with strenuous outdoor jobs, and those with chronic respiratory and pulmonary illnesses such as asthma and COPD. The complicated territory and sheer size of the fires in Canada hinder their management, so it is likely the Midwest will continue experiencing on-again off-again poor air quality days in the coming weeks as long as the fires keep burning.

Late June Derecho

The switch from a dry June to wet and active July happened on June 29. That day, several rounds of severe storms moved through central and southern Illinois, producing large hail and a few tornadoes. The most destructive impacts from the storm, though, came from the derecho it produced: https://www.weather.gov/ilx/june29_derecho. A derecho is a widespread, long-lived windstorm that is associated with a series of strong thunderstorms. Most derecho impacts come from its incredibly strong straight-line winds. The June 29 event produced widespread 70–80 mph wind gusts from the Quad Cities to Danville, including one personal weather station in Taylorville that measured 101 mph wind.

The derecho caused substantial damage to trees, homes, and buildings, and caused widespread power outages. Perhaps some of the worst storm damage was in Springfield, which had an estimated $20 million in damages alone (Figure 9). The derecho caused significant crop damage across central Illinois, although not nearly to the extent of the infamous 2020 derecho that moved across Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana. This year’s derecho happened earlier in the growing season when corn was shorter and less brittle, and thankfully, it was much weaker than the 2020 event.

Speaking of Severe Weather…

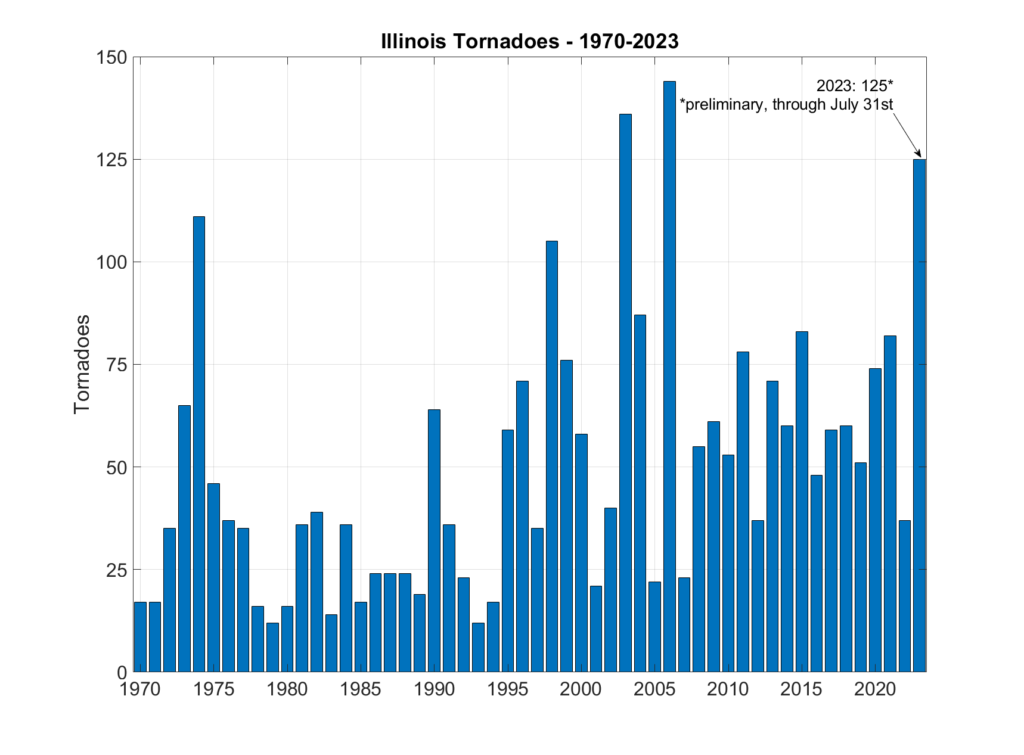

No matter if we’re in Cairo, Egypt or Cairo, Illinois, drought is caused by a lack of precipitation over a period sufficiently long as to cause impacts. Because the same storms that bring severe weather also account for a big chunk of our warm season precipitation, summer drought years also tend to have a dearth of tornadoes, hail, and storm winds, but not this year. As of July 31, Illinois has had 125 tornadoes in 2023 reported by the Storm Prediction Center. Importantly, this is a preliminary total and may be adjusted later this year as reports are refined. However, if that total is accurate, it would give this year the third highest tornado frequency on record for any year (Figure 10). The current annual tornado record for Illinois is 142 in 2006.

Outlooks

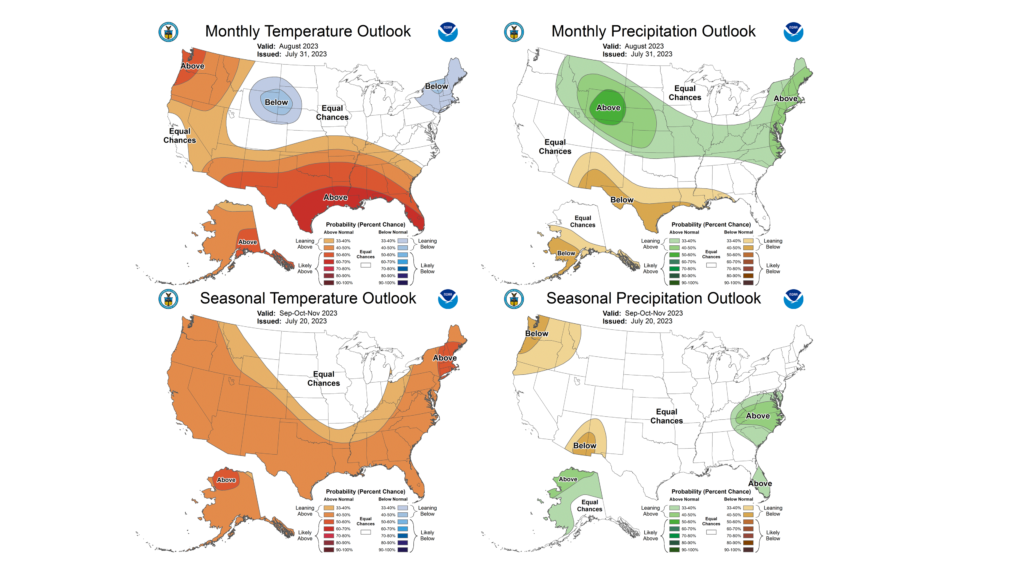

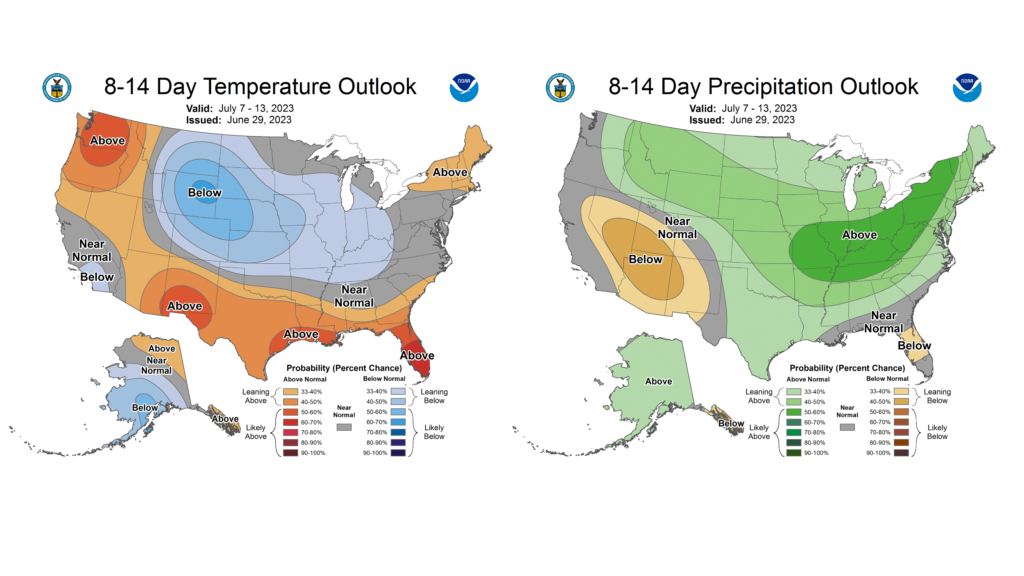

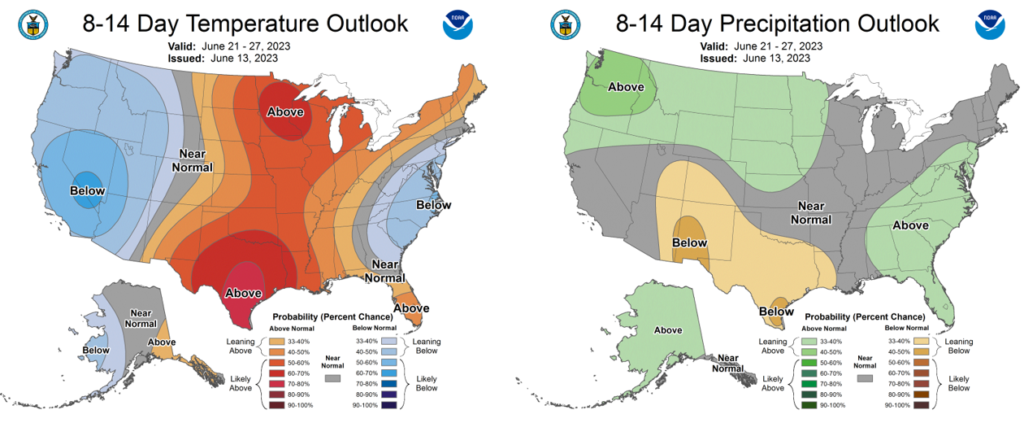

August is the beginning of the end of summer but can certainly bring its fair share of heat. August is also an important month for finishing crops as we move toward fall. The most recent Climate Prediction Center outlooks for August show equal chances of above and below normal temperatures in much of the state, with higher odds of above normal temperatures in the southeast U.S. (Figure 11). Precipitation outlooks are leaning wetter than normal for much of the state, which would help continue the march out of drought in Illinois.

The bottom row in Figure 11 shows temperature and precipitation outlooks for the climatological fall season, September–November. The outlooks are decidedly equivocal, with equal chances of warmer, cooler, wetter, and drier than normal conditions in fall. It’s important to note that August to October is the “heart” of tropical storm season in the Atlantic, but the monthly and seasonal outlooks for the Midwest do not include any prediction of tropical storm frequency.