[edited 3/8/16 based on feedback]

There have been some mention in the ag media about the linkage between above-average November-December precipitation and lower below-trend corn yields for the next summer (usually understood to be related to some form of drought). It’s an intriguing case because the drought of 2012 was preceded by a wet November-December. However, when you dig into the statistics, the relationship is more complicated.

For this comparison I looked at the 11 wettest November-December events for the Corn Belt (map at bottom)and the US corn yield from the USDA. I picked the top 11 wettest because it gives us 10 previous cases to examine.

The 11 Wettest Corn-Belt November-December

- 2015 with 7.17 inches

- 1982 with 6.59 inches

- 1983 with 5.95 inches

- 1909 with 5.93 inches

- 1985 with 5.78 inches

- 1931 with 5.76 inches

- 1992 with 5.53 inches

- 1972 with 5.25 inches

- 1990 with 4.98 inches

- 2011 with 4.94 inches

- 1973 with 4.83 inches

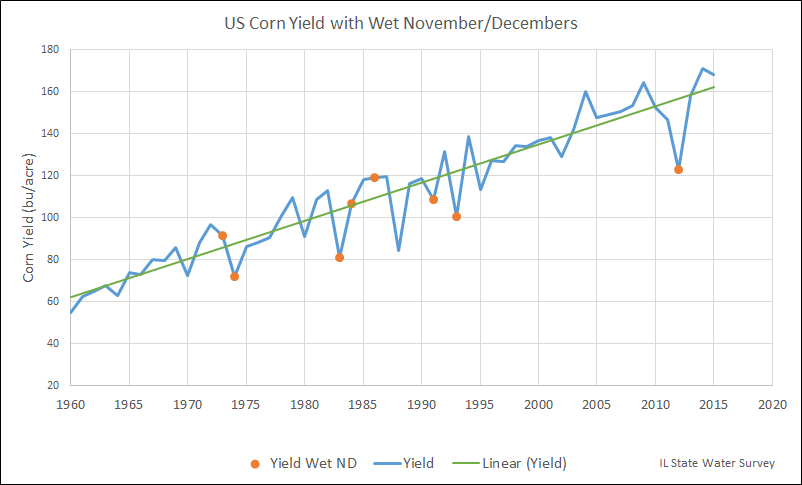

Here are how the corn yields for the growing season following a wet November-December looks like (orange dots), compared to all corn yields (blue line), and the yield trend (green line). We did not consider yields in 1910 or 1932 since those predated modern hybrids. Of the remaining 8, 1974, 1983, 1991, and 2012 experienced below-trend yields from drought and 1993 experienced below-trend yields from flooding.

It is important to point out that the growing season in 1983 was entirely different from 1974, 1991, and 2012. The 1974, 1991, and 2012 growing seasons were fully developed agricultural droughts that had developed over several months. On the other hand, the low yields in 1983 were the result of several hot, dry weeks in July and August. This occurred after a wet spring that probably inhibited good root development.

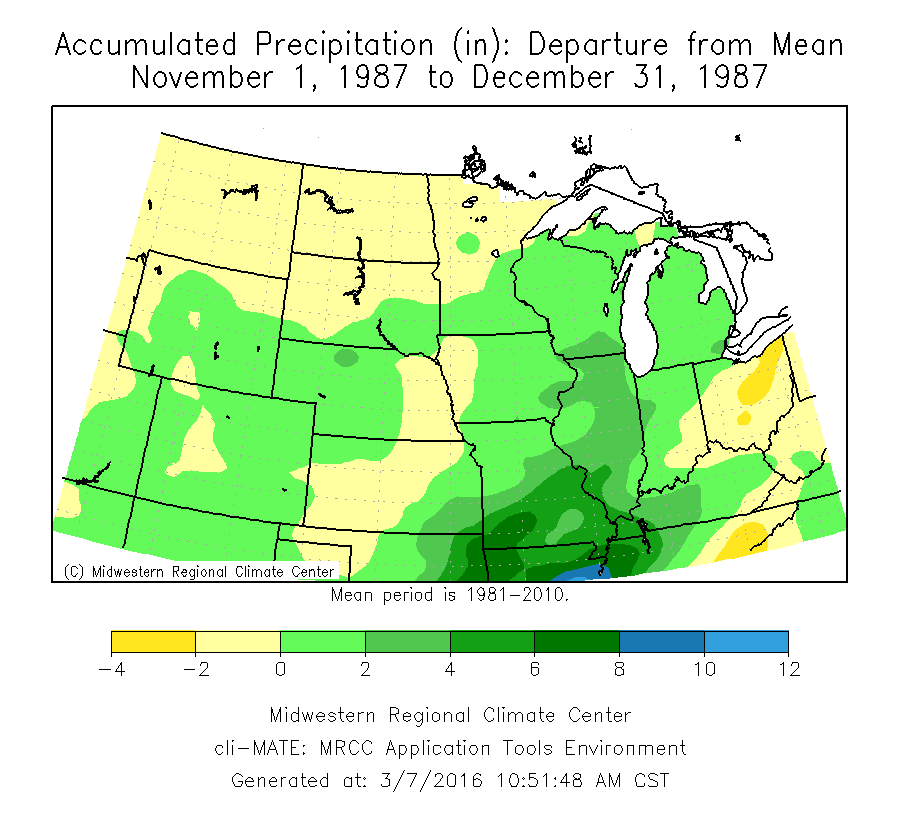

The drought of 1988 is missing in this analysis because not all of the core region of Corn Belt was wet in November-December 1987 (precipitation departure map below). Illinois was certainly wet but areas to the east and west were not.

Conclusion

In classic statistics, one of the struggles with any analysis is “do you have enough samples to draw reliable conclusions?” In this case, of the ten wettest November-December cases, two cases occurred too early in the corn yield records.So, you might conclude from this that you have a 63 percent chance at below-trend US corn yields this year. However, the path to those below-trend yields is not consistent. It picked up three agricultural droughts (1974, 1991, and 2012), but also picked up one flood (1993) and missed one drought (1988), and got a complicated wet-spring/dry-summer combo in 1983. Furthermore, without a clear meteorological mechanism in place to explain the apparent connection between November-December and the next growing season, it remains only a statistical relationship at this point.

As the commodity brokers like to say, “Past performance is not always an indicator of future results.” I think I would lean towards that one. With the Corn Belt currently drought free, recharged soil moisture reserves, and our current wet pattern, I’m not as concerned about drought for now, at least not in Illinois. In recent years, wet conditions have been the bigger challenge.

Notes:

The Corn Belt, as defined by the National Centers for Environmental Information, and used to pull the precipitation data for this analysis.

Jim, one key factor that this study does not consider is farm drainage. In the buckle of the corn belt, there has been a significant amount of new or enhanced drainage installed on farm fields in the past 5 years. I think that ameliorates the impact of wetter soils at this time of year.

I like that term “buckle of the Corn Belt”. I agree that improved drainage has helped reduce the impact. I have seen a number of fields this winter that were freshly tiled.